For those who grew up in the suburbs, moving into the city is a major cultural shift. For many, the appeal of the city lies in the wide menu of options available to you to choose from: dinner at the trendy new food truck, brunch at the cute cafe, climbing at the local rock climbing gym, etc. There’s nothing wrong, per se, with taking advantage of that menu of options and enjoying the city! However, I’ve noticed a common problem that arises from ex-suburbanites moving into an urban environment.

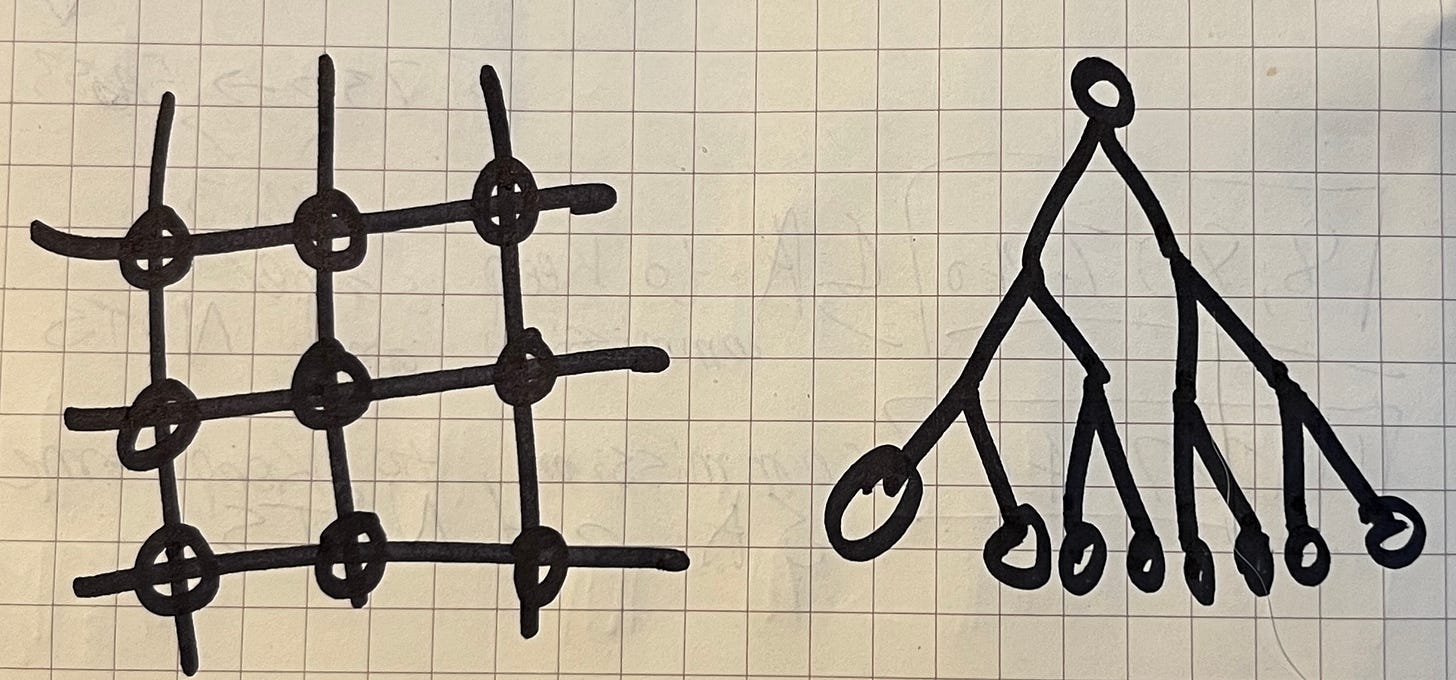

Cities are dense, sprawling tangles of activity. Suburbs, on the other hand, are organized around high-speed roads and highways, strip malls, subdivisions, and cul-de-sacs. While suburbs certainly have more neighbors at closer proximity than fully rural areas, the neighborhoods of suburbs are dramatically more controlled and hierarchical than the lattices of city networks. Think of it this way: suburbs tightly plan and control the points of connection between neighborhood nodes (think wide roads with few large intersections) while cities promote a much larger number of connections between the nodes (more intersections of all scales, more street corners with more stores, a wider variety of street and alley sizes). “Higher density” is often how cities are described, but it’s not just more people: it’s more opportunities for interaction. In cities, it’s more likely that occupants bump into each other. And where there are more encounters, there’s more surprise.

Surprise is fundamental to urban life. The more unique actors that are present in your environment, the more the unexpected will interrupt your routine. For many ex-suburbanites, their habits retain the same dynamics as their former system of living: car centered, highly routinized, closed to the random surprising encounters inherent to cities. While many folks learn the ways of the city, many others don’t. This cultural shift is what some people are thinking of when they use the term “gentrification:” a “suburbanization” of habits, not just a rise in rents.

I know the whole “urban vs rural” debate often swirls around how much green space you want/need, but I’d propose Surprise as a more significant conversation to have! Are you open to and energized by the surprise of city life? Do you enjoy opening yourself to the shifting tides of your street?

Like I said earlier, many people are attracted to the menu of options of the city. But the problem arises when those new urbanites treat the city as if it’s a suburb: only participating in that which you choose, rather than openly engaging the city’s breadth. Life in a city isn’t like ordering from a menu: sometimes, you don’t choose what you engage with. Sometimes, the city presses itself upon you, and you must respond. For better and for worse, the city interrupts. The city surprises.

Sometimes those surprises are pleasant, like meeting your neighbors’ dogs as they walk by. Or giving the local corner store’s $6 hoagie a shot for lunch, and finding it blows the trendy fancy millennial hoagie out of the water. Or finding the perfect end table for your living room sitting on the curb waiting for trash pickup. Or for your pickup!

Sometimes those surprises are unpleasant. Domestic disputes spilling into the street, cop activity, late night fireworks.

Either way, it’s a misunderstanding to assume life in the city will be as orderly as life in the suburbs. The suburbs sit back and wait for you to choose. The city comes at you; the city surprises.

This raises a few questions: what kind of surprise can you open yourself to? What kinds of surprise do you need to temper and reduce? Which surprises vivify and enrich you? How frequently do you just wait on the city, letting yourself experience whatever it has in store? Where in your life — and I mean physically, geographically — are you routinely surprised? Why do you think that is? Do you enjoy experiencing that rupture in your expectations?

For me, it’s when I walk my dogs to the local park. How often do you visit your local park? I’ve got 2 dogs (@momozukofomo on Instagram) so I’m there pretty much every day. I’ve met friends and future clients there, but also had some ugly and frustrating encounters here as well. Sometimes people are unexpectedly understanding and joyful, sometimes they’re surprisingly prejudiced and angry. I mean hey, it’s Philly. Sifting through those unexpected and surprising encounters is part of what makes city life as vibrant and meaningful as it is. For some, it’s more exhausting than it is enriching. If that’s you, no shame! Now you know! As you look for a home, make sure to take that into account. If you (like me) are excited to wade through the surprising collisions of the lattice network of city life, then meet me at the park and let’s talk.

Open and experimental

In his book Building and Dwelling, Richard Sennett describes the experimental strategies he encountered while working at MIT:

In a general way, researchers work within a well-worn orbit when performing an experiment to prove or disprove a hypothesis; the original proposition governs procedures and observations; the denouement of the experiment lies in judging whether the hypothesis is correct or incorrect. In another way of experimenting, researchers will take seriously unforeseen turns of data, which may cause them to jump tracks and think "outside the box." They will ponder contradictions and ambiguities, stewing in these difficulties for a while rather than immediately trying to solve them or sweep them aside. The first kind of experiment is closed in the sense it answers a fixed question: yes or no. Researchers in the second kind of experiment work more openly in that they ask questions which can't be answered in that way. (p. 4)

I love this distinction between "open" versus "closed" experimentation. Another way of articulating Sennett's point: open experimentation is adaptive and listens to confusing or surprising data; closed experimentation hews to the hypothesis and strains for useful data. When faced with something unexpected, “open” says “this is interesting, let’s keep going and see where it goes!” “Closed” responds “this wasn’t what I was looking for, let’s try again!” Open is improv comedy, Closed is sketch comedy. Both have their value, of course! But in the context of city life, an "open" posture towards the surprises of the city can be enriching and healthy. Maintaining too “closed” an attitude to the city will quickly become overwhelming. Rather than forcing the chaotic urban lattice networks into orderly suburban boundaries, living in the city means learning to adapt to the shifting tides and surprises. If order is what you require for your home, then the city is unlikely to satisfy you. Moreover, your neighbors will almost certainly quickly grow sick of your attempts to wrestle the city to your predictable script. When you move to the city, you enter its mix and must learn to adapt to it.

Surprise and the divine

Ultimately, no matter how much you may seek it out or avoid it, surprise arrives on its own timing. Surprise is always out of our control. There’s a degree to which, via practices like mindfulness meditation and paying attention, even the most familiar can appear strange or new to our sense. But in a different sense, surprise has more to do with revelation than attention. When we experience surprise, we are encountering the otherness of the world (and some would say the divine!) at the level of our expectations and understanding. Surprise, whether you like it or not, is always an indicator of the frontier of your understanding. Of course not all surprises are created equal, and often surprises are painful and unfortunate, but the experience of being surprised always demands to be taken seriously.

Personally, it’s been my relationship with surprise that’s been characteristic of my relationship to faith and belief and God over the last few years. If you read theology, then Karl Barth has been helpful for me. Similarly, life in the city has become for me something of a spiritual discipline. Encountering the unpredictable and surprising is, in its way, a reflection of not just myself but of the larger energy and power of the world — or even God. Learning to attend to and listen to not just the phenomena that provoke surprise but to the feeling of surprise itself has been meaningful for me.

Can the divine be predictable? Do you encounter God or a higher power in surprise? When your container of belief of how the world works or is organized gets cracked open, how do you respond?

Share this post